|

NA LISTI Od 04.8.2010.g. /

LISTED SINCE August 4th, 2010 among leading European magazines: |

All Rights Reserved

Publisher online and owner: Sabahudin Hadžialić, MSc Sarajevo & Bugojno, Bosnia and Herzegovina MI OBJEDINJUJEMO RAZLIČITOSTI... WE ARE UNIFYING DIVERSITIES |

Interview - Tatjana Debeljački vs Paul Casey,

Cork, Ireland - 12.6.2012.

.

Paul Casey was born in Cork, Ireland in 1968. He grew up and has lived between Ireland, Zambia and South Africa, working mostly in film, multimedia and teaching. He taught screenwriting at the Nelson Mandela University, where he convened the greater Port Elizabeth Poetry Competition in three languages and four age groups. His poems are published in journals and anthologies in Ireland, South Africa, the US and China. His chapbook of longer poems It’s Not all Bad (Heaventree Press) was published in 2009. In October 2010 his poetry-film The Lammas Hireling, after the poem by Ian Duhig, premiered at the Zebra poetry-film festival in Berlin, and has since been screened at festivals worldwide, including StanZa in Edinburgh and Sadho in New Delhi. His debut collection home more or less was published by Salmon Poetry in May 2012. He is the founder and organiser of the Ó Bhéal reading series in Cork, where he lives.

Some Links

Salmon Poetry page – http://www.salmonpoetry.com/details.php?ID=261&a=222

Ó Bhéal – www.obheal.ie

Facebook Page – http://www.facebook.com/pcpoet

An article on Journal.ie - http://www.thejournal.ie/readme/column-i-was-homeless-for-months-because-i-couldn%E2%80%99t-prove-i-was-irish/

Some Links

Salmon Poetry page – http://www.salmonpoetry.com/details.php?ID=261&a=222

Ó Bhéal – www.obheal.ie

Facebook Page – http://www.facebook.com/pcpoet

An article on Journal.ie - http://www.thejournal.ie/readme/column-i-was-homeless-for-months-because-i-couldn%E2%80%99t-prove-i-was-irish/

INTERVIEW - INSPIRED BY THE WONDROUS

Is your work skilful, often entertaining, simple and changeable?

Inasmuch as I have spent over ten years closely exploring poetic forms, and writing in a variety of different forms, my work has become a lot more skilful and concise. There’s much excitement in achieving this during the writing process. I am always driven to make the poem as perfect as possible. Sometimes poems only come after much time and great care, and far less often they arrive very quickly, already in near-perfect form. Knowing the craft of poetry, and a lot of reading and practice, seem to be essential here. When the poem arrives it should be able to decide its form with ease. Knowing when to use alliteration or a caesura, or being able to sense the gender of endings, ought to be natural impulses. Whether to write in free verse, a villanelle or sonnet, I enjoy discovering whichever shape the poem likes best. The poet is the natural limit of the poem. Improve the poet and the poetry improves. Of course this all means nothing without engaging directly with the world at large, with people and relationships, with nature, events of the everyday, the great themes of life, etc.

Where possible, I enjoy allowing a unique voice to give birth to each poem. Yes, it’s all in the voice of one poet, yet when the poet experiences different narratives and explores new territories, the song within each poem becomes different. I also have six languages to draw upon, which I hope has given my work an advantage. My poetry is changeable in this respect, and can be either simple or complex in composition, but always serving its own peculiar vision. I try to make all my poems entertaining for someone, for an imagined audience sometimes, or for one person, or even just for myself. I think it’s up to readers and audiences to decide whether one’s work is skilful, entertaining etc. I’ve held five hundred people in silence for ten minutes with a poem, which has given me a certain confidence that my work is, or can be entertaining.

Can you tell us something about your hometown and growing up?

I grew up between Ireland (at school in Kildare and partly in Cork), Zambia (in Kitwe and Lusaka) and South Africa (Johannesburg), attending school in all three countries. While these environmental and cultural contrasts were magnificently colourful, most of my informative cultural references have been Irish. During my early years in Zambia we lived and socialized within an ‘ex-pat bubble’ of Irish festivity, gatherings, song, stories and hurling matches. It was almost like living in an extra county of Ireland. During my first eleven years I spent a lot of time in the swimming pool under the hot Zambian sun, or playing in the streets and streams of Cork, or in the woods of the Irish midlands. Then I was quite suddenly immersed into the Apartheid world of urban South Africa (1979). Culture-shocked, I grappled with that world for ten years. Then I began to travel more widely, working in different jobs on a number of continents, until over the years I finally succumbed to the ever-growing pull, the slow but sure tug, back to the shores of my birth.

Which of your works do you consider the best and why?

That’s not an easy one. My longest poem, It’s not all Bad, which is a satire on the mainstream media, is a ten-minute performance piece which I wrote in 2002. It arrived all in one go – the poem was finished in thirty minutes (aside from a few minor nips and tucks) and has somehow never failed to hold the attention of an audience. I thought that to be my best poem until I wrote another long poem, incorporating a number of different forms -Scannánaigh the Poet, a satire on the commercial film industry, which contains a lot more variety and skill (I don’t write a lot of satire by the way).

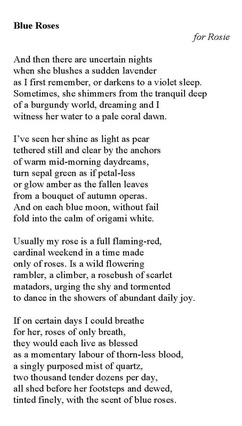

Since then I’ve written other poems that I consider to be among my best, each very different and difficult to compare. Perhaps Anginyamalalanga, (I haven’t Disappeared) a Zulu poem I wrote when in South Africa, because the sounds of Africa come to life in the poem so powerfully, or Painless, an autobiographical poem I wrote about my dentists. For very different reasons my most recent favourites include Rain in the Glen, for invoking the famous Irish hurling player - Christy Ring, Blue Roses, a love poem and Ar Shiúl leis na Síoga (Away with the Faeries), my first poem written in the Irish language.

There is an air of eternity in poetry and the poet's visions are unpredictable?

Yes and yes. It’s like the poem is often not really my own, but sent through me by a distant, elusive spirit, from an eternal and capricious place, a place as infinite as the multiverse of human dreams. The horizons of the imagination seem to ever deepen when the poem happens, and almost anything seems possible. I find the most courageous part of writing is in remaining open to this unpredictability, so that the visions may arrive freely. My dentist poem became vivid while sitting in the dentist chair, as I listened to a dental assistant charting off my teeth. My Zulu poem arrived in the middle of the night, and I sat bolt upright in bed, the entire image held within a single word, ukunyamalala – the Zulu word meaning ‘to disappear’, the poem looming before me like a ghost wanting to become physical. My Irish poem arrived when listening to a stream in County Cork, and it sang to me in the voice of the fairy folk.

Poets express themselves in the smallest number of words?

Yes, poets should be economical, whenever possible. I’ve met and read a great deal of poets whose work is overwritten and consequently too loose. How many potentially excellent poems have been hurt in this way? The best poems are never superfluous, but having said that, some subject matter and approaches to poetry work well with repetition and the echoes of parallelism. I find that poems about the sea for example, work well with repetition. I write long poems and short poems, but within each line, each phrase, the writing should be concise. Density is a prime ingredient of potency.

Special travelling experiences?

I’ve been on the road and in the sky since an early age, and have always loved the excitement of travel. As a young boy I would travel by plane fromIreland to Zambia and back with my schoolmates, and a strong sense of adventure grew from there. The majority of my travelling as an adult has been solitary, and being able to take in the world on my own terms, has always been a special experience. I have done much walking and hiking through the countries I have lived in or visited. And much around Ireland, which never loses that magical sense of having a different world waiting around each bend, or a new surprise hiding over the next hill. I hitchhiked from Tokyo to Hokkaido, from Grindelwald to Barcelona, from Johannesburg toWindhoek. Each journey has inspired me. Being immersed as an individual in the world always gives me a sense of privilege in being its witness. Until I start to miss human contact.

What does your average working day look like?

I’m not a regular writer, although I’m usually up between 6am and 8am, and I write most often during this time. Then I move onto reading the news and answering correspondence. Then onto whatever project I’m working on. Sometimes a poem will find me in the middle of the day and I’ll have to drop what I’m doing to catch it. Poems can arrive at any time, and they all shout ‘Carpe-Diem!’. I’m very much a flexi-time person, which gives me the freedom to travel when I need to. I learned early that I can’t work in a full-time 9-5 position without trying to take over the whole company - so outside of my own work I’ve stuck to working seasonally, or under contract - mostly in teaching, multimedia and film. Next to these, I’m involved in arts and project facilitation, and occasional workshops. Work arrives in varying degrees of intensity. One month I may be at the computer eighteen hours per day, the next month it may be six.

I am the director of Ó Bhéal (Irish for: from the mouth / by word of mouth) - Cork’s weekly poetry reading series. I programme fifty events per year, each showcasing one or more guest poets from around Ireland or overseas. I work more by a weekly routine than by a daily one. Sundays and Mondays are always ‘Ó Bhéal’ days, updating websites, scheduling and arranging logistics. Each year is scattered with arts funding applications and administrative deadlines, and I’m usually involved in extra projects to fill the gaps, like making a poetry-film, or editing.

What inspires you: love, world affairs, writing itself, achievements?

All of the above. I look for inspiration everywhere. I am inspired by the wondrous, the magical things of the world, by beauty, the human spirit, by courage. By worlds that reveal themselves through different languages. The language of birds and bonsai trees. I am inspired by good literature, whether historical, contemporary or fictional. And by good poetry. My own writing and achievements do play a part, in that they urge me towards new heights. Waking up every morning is inspiring to me. I’m often inspired by dreams. By love, certainly. Love fuels the imagination more than anything I know.

What are you doing at the moment and what are your plans for the future?

At the moment I’m working on a sign-poetry project for the deaf community in Cork, to help in the creation of poetry using sign-language. I’m fascinated as to how poetry can exist outside of words. I’ve just finished a poem I was commissioned to write for an elderly home in Cork, integrating messages that were written on a ‘talking’ wall, into a rhyming ballad. I’ll be giving another series of workshops for the elderly in July.

As my new collection home more or less has just been published by Salmon Poetry, I’m in the middle of a tour of readings around Ireland andEurope. My plans for the future? Writing as much as I can. I’m on the lookout for residencies and readings, and I hope to make another small poetry-film over the next year.

Is your work skilful, often entertaining, simple and changeable?

Inasmuch as I have spent over ten years closely exploring poetic forms, and writing in a variety of different forms, my work has become a lot more skilful and concise. There’s much excitement in achieving this during the writing process. I am always driven to make the poem as perfect as possible. Sometimes poems only come after much time and great care, and far less often they arrive very quickly, already in near-perfect form. Knowing the craft of poetry, and a lot of reading and practice, seem to be essential here. When the poem arrives it should be able to decide its form with ease. Knowing when to use alliteration or a caesura, or being able to sense the gender of endings, ought to be natural impulses. Whether to write in free verse, a villanelle or sonnet, I enjoy discovering whichever shape the poem likes best. The poet is the natural limit of the poem. Improve the poet and the poetry improves. Of course this all means nothing without engaging directly with the world at large, with people and relationships, with nature, events of the everyday, the great themes of life, etc.

Where possible, I enjoy allowing a unique voice to give birth to each poem. Yes, it’s all in the voice of one poet, yet when the poet experiences different narratives and explores new territories, the song within each poem becomes different. I also have six languages to draw upon, which I hope has given my work an advantage. My poetry is changeable in this respect, and can be either simple or complex in composition, but always serving its own peculiar vision. I try to make all my poems entertaining for someone, for an imagined audience sometimes, or for one person, or even just for myself. I think it’s up to readers and audiences to decide whether one’s work is skilful, entertaining etc. I’ve held five hundred people in silence for ten minutes with a poem, which has given me a certain confidence that my work is, or can be entertaining.

Can you tell us something about your hometown and growing up?

I grew up between Ireland (at school in Kildare and partly in Cork), Zambia (in Kitwe and Lusaka) and South Africa (Johannesburg), attending school in all three countries. While these environmental and cultural contrasts were magnificently colourful, most of my informative cultural references have been Irish. During my early years in Zambia we lived and socialized within an ‘ex-pat bubble’ of Irish festivity, gatherings, song, stories and hurling matches. It was almost like living in an extra county of Ireland. During my first eleven years I spent a lot of time in the swimming pool under the hot Zambian sun, or playing in the streets and streams of Cork, or in the woods of the Irish midlands. Then I was quite suddenly immersed into the Apartheid world of urban South Africa (1979). Culture-shocked, I grappled with that world for ten years. Then I began to travel more widely, working in different jobs on a number of continents, until over the years I finally succumbed to the ever-growing pull, the slow but sure tug, back to the shores of my birth.

Which of your works do you consider the best and why?

That’s not an easy one. My longest poem, It’s not all Bad, which is a satire on the mainstream media, is a ten-minute performance piece which I wrote in 2002. It arrived all in one go – the poem was finished in thirty minutes (aside from a few minor nips and tucks) and has somehow never failed to hold the attention of an audience. I thought that to be my best poem until I wrote another long poem, incorporating a number of different forms -Scannánaigh the Poet, a satire on the commercial film industry, which contains a lot more variety and skill (I don’t write a lot of satire by the way).

Since then I’ve written other poems that I consider to be among my best, each very different and difficult to compare. Perhaps Anginyamalalanga, (I haven’t Disappeared) a Zulu poem I wrote when in South Africa, because the sounds of Africa come to life in the poem so powerfully, or Painless, an autobiographical poem I wrote about my dentists. For very different reasons my most recent favourites include Rain in the Glen, for invoking the famous Irish hurling player - Christy Ring, Blue Roses, a love poem and Ar Shiúl leis na Síoga (Away with the Faeries), my first poem written in the Irish language.

There is an air of eternity in poetry and the poet's visions are unpredictable?

Yes and yes. It’s like the poem is often not really my own, but sent through me by a distant, elusive spirit, from an eternal and capricious place, a place as infinite as the multiverse of human dreams. The horizons of the imagination seem to ever deepen when the poem happens, and almost anything seems possible. I find the most courageous part of writing is in remaining open to this unpredictability, so that the visions may arrive freely. My dentist poem became vivid while sitting in the dentist chair, as I listened to a dental assistant charting off my teeth. My Zulu poem arrived in the middle of the night, and I sat bolt upright in bed, the entire image held within a single word, ukunyamalala – the Zulu word meaning ‘to disappear’, the poem looming before me like a ghost wanting to become physical. My Irish poem arrived when listening to a stream in County Cork, and it sang to me in the voice of the fairy folk.

Poets express themselves in the smallest number of words?

Yes, poets should be economical, whenever possible. I’ve met and read a great deal of poets whose work is overwritten and consequently too loose. How many potentially excellent poems have been hurt in this way? The best poems are never superfluous, but having said that, some subject matter and approaches to poetry work well with repetition and the echoes of parallelism. I find that poems about the sea for example, work well with repetition. I write long poems and short poems, but within each line, each phrase, the writing should be concise. Density is a prime ingredient of potency.

Special travelling experiences?

I’ve been on the road and in the sky since an early age, and have always loved the excitement of travel. As a young boy I would travel by plane fromIreland to Zambia and back with my schoolmates, and a strong sense of adventure grew from there. The majority of my travelling as an adult has been solitary, and being able to take in the world on my own terms, has always been a special experience. I have done much walking and hiking through the countries I have lived in or visited. And much around Ireland, which never loses that magical sense of having a different world waiting around each bend, or a new surprise hiding over the next hill. I hitchhiked from Tokyo to Hokkaido, from Grindelwald to Barcelona, from Johannesburg toWindhoek. Each journey has inspired me. Being immersed as an individual in the world always gives me a sense of privilege in being its witness. Until I start to miss human contact.

What does your average working day look like?

I’m not a regular writer, although I’m usually up between 6am and 8am, and I write most often during this time. Then I move onto reading the news and answering correspondence. Then onto whatever project I’m working on. Sometimes a poem will find me in the middle of the day and I’ll have to drop what I’m doing to catch it. Poems can arrive at any time, and they all shout ‘Carpe-Diem!’. I’m very much a flexi-time person, which gives me the freedom to travel when I need to. I learned early that I can’t work in a full-time 9-5 position without trying to take over the whole company - so outside of my own work I’ve stuck to working seasonally, or under contract - mostly in teaching, multimedia and film. Next to these, I’m involved in arts and project facilitation, and occasional workshops. Work arrives in varying degrees of intensity. One month I may be at the computer eighteen hours per day, the next month it may be six.

I am the director of Ó Bhéal (Irish for: from the mouth / by word of mouth) - Cork’s weekly poetry reading series. I programme fifty events per year, each showcasing one or more guest poets from around Ireland or overseas. I work more by a weekly routine than by a daily one. Sundays and Mondays are always ‘Ó Bhéal’ days, updating websites, scheduling and arranging logistics. Each year is scattered with arts funding applications and administrative deadlines, and I’m usually involved in extra projects to fill the gaps, like making a poetry-film, or editing.

What inspires you: love, world affairs, writing itself, achievements?

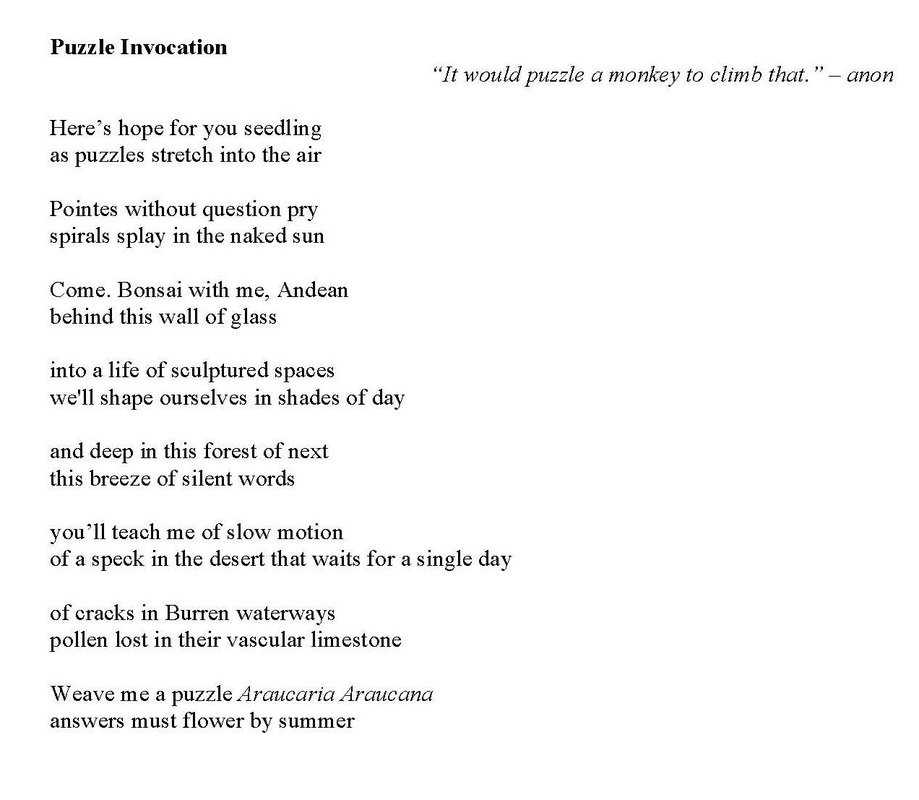

All of the above. I look for inspiration everywhere. I am inspired by the wondrous, the magical things of the world, by beauty, the human spirit, by courage. By worlds that reveal themselves through different languages. The language of birds and bonsai trees. I am inspired by good literature, whether historical, contemporary or fictional. And by good poetry. My own writing and achievements do play a part, in that they urge me towards new heights. Waking up every morning is inspiring to me. I’m often inspired by dreams. By love, certainly. Love fuels the imagination more than anything I know.

What are you doing at the moment and what are your plans for the future?

At the moment I’m working on a sign-poetry project for the deaf community in Cork, to help in the creation of poetry using sign-language. I’m fascinated as to how poetry can exist outside of words. I’ve just finished a poem I was commissioned to write for an elderly home in Cork, integrating messages that were written on a ‘talking’ wall, into a rhyming ballad. I’ll be giving another series of workshops for the elderly in July.

As my new collection home more or less has just been published by Salmon Poetry, I’m in the middle of a tour of readings around Ireland andEurope. My plans for the future? Writing as much as I can. I’m on the lookout for residencies and readings, and I hope to make another small poetry-film over the next year.

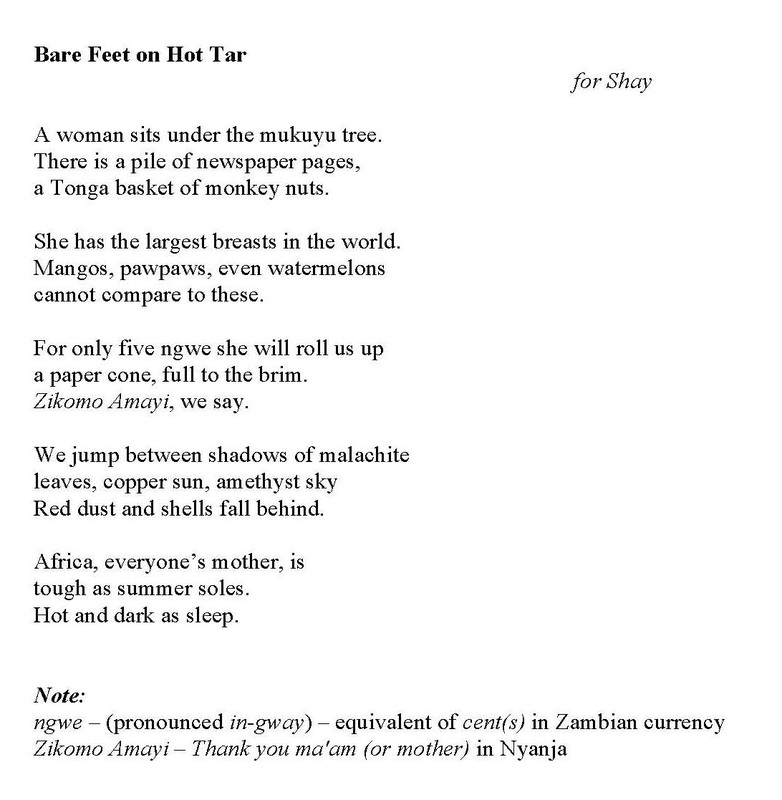

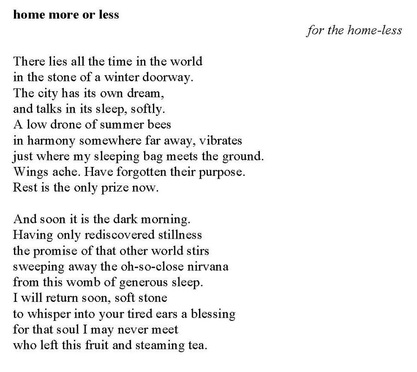

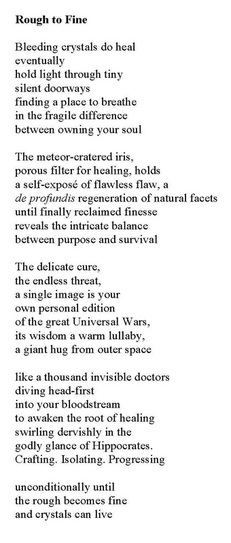

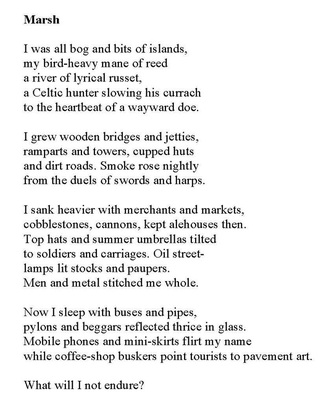

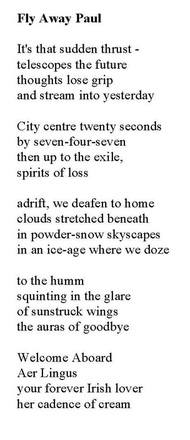

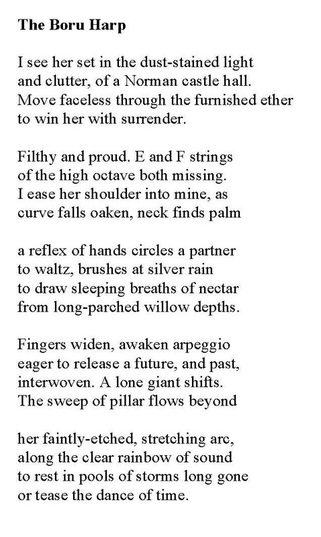

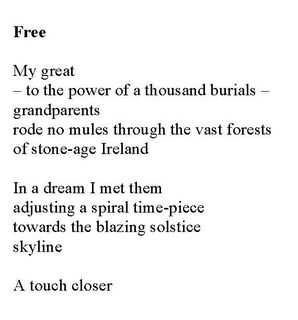

Poems - Paul Casey

Narudžba knjiga / Purchasing of the books / Bücher bestellen

.

Copyright © 2014 DIOGEN pro cultura magazine & Sabahudin Hadžialić

Design: Sabi / Autors & Sabahudin Hadžialić. Design LOGO - Stevo Basara.

Freelance gl. i odg. urednik od / Freelance Editor in chief as of 2009: Sabahudin Hadžialić

All Rights Reserved. Publisher online and owner: Sabahudin Hadžialić

WWW: http://sabihadzi.weebly.com

Contact Editorial board E-mail: [email protected];

Narudžbe/Order: [email protected]

Pošta/Mail: Freelance Editor in chief Sabahudin Hadžialić,

Grbavička 32, 71000 Sarajevo i/ili

Dr. Wagner 18/II, 70230 Bugojno, Bosna i Hercegovina

Design: Sabi / Autors & Sabahudin Hadžialić. Design LOGO - Stevo Basara.

Freelance gl. i odg. urednik od / Freelance Editor in chief as of 2009: Sabahudin Hadžialić

All Rights Reserved. Publisher online and owner: Sabahudin Hadžialić

WWW: http://sabihadzi.weebly.com

Contact Editorial board E-mail: [email protected];

Narudžbe/Order: [email protected]

Pošta/Mail: Freelance Editor in chief Sabahudin Hadžialić,

Grbavička 32, 71000 Sarajevo i/ili

Dr. Wagner 18/II, 70230 Bugojno, Bosna i Hercegovina